Shingeki no Kyojin,

or Attack on Titan in English, is a

Japanese manga and corresponding anime series, about giant humanoids (Titans) with

an insatiable hunger for human flesh. Surviving humanity has retreated within a

series of walls, until one day the Titans breach the walls and the humans are

forced to act lest they be wiped out forever.

Looking at Shingeki no

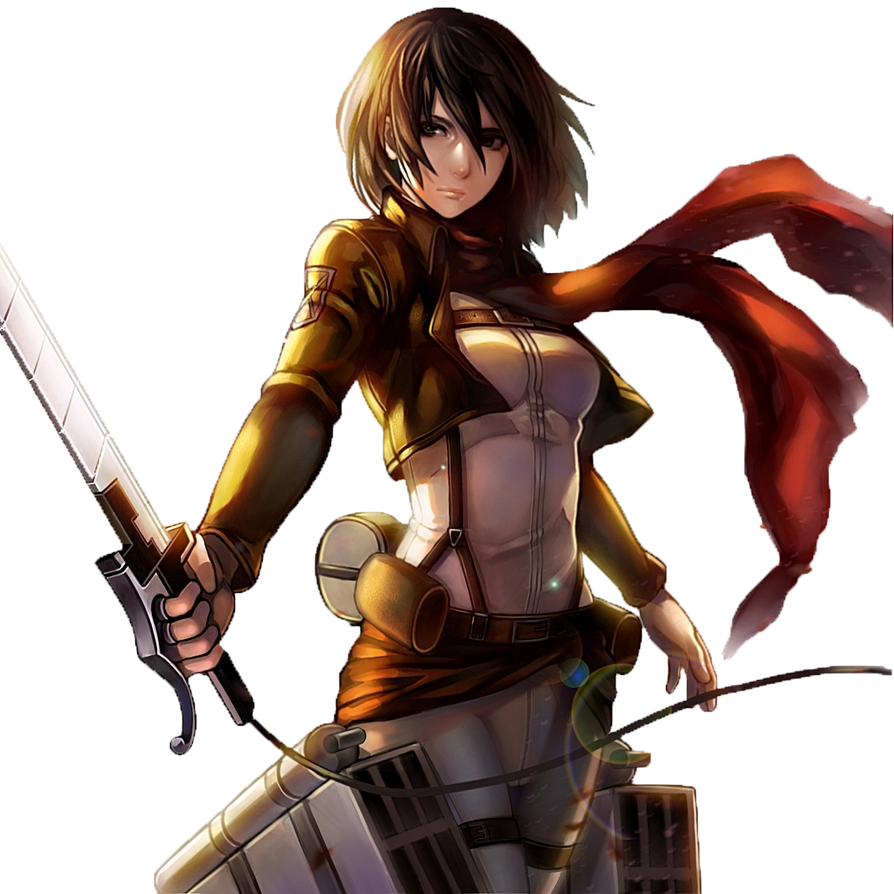

Kyojin, it’s easy to see where Hollywoodization has come in. One character

is the last Asian human alive amongst a presumably European and American

population, playing upon an oft used storyline in American cinema. Additionally,

large battle sequences and set pieces often occur, reminiscent of those in the

Hollywood blockbuster, resulting in dramatic effects on the storyline including

major character deaths.

Mikasa Ackerman, the last Asian on Earth (Source: Deviantart)

The anime’s score also has a notable mixture of Asian and

Western influences, not dissimilar from Pacific

Rim’s soundtrack, a film also known for blending Asian and Western

flavours.

Shingeki no Kyojin OST mini-mix (Source: YouTube)

It’s obvious that “globalization’s homogenizing and heterogenizing tendencies” (Klein 2004, p. 372), are producing spliced products that are a new genre unto themselves and we as consumers from both the Asian and Western markets will reap the rewards with amazing cinema and television to come.

Sources:

Klein, Christina 2004, ‘Martial arts and globalisation of US and Asian film industries’, Comparative America Studies, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 360-384.